Policymakers should listen to young activists

By Robert Gottlieb | China Daily Global | Updated: 2019-12-16 09:24

Two years ago, while in Nanjing, China, I attended an environment-themed fashion show organized by students from Nanjing University, Chinese University of Hong Kong and Taiwan University.

The students mimicked a type of fashion walk down the aisle, wearing clothes made from reused materials. It was great fun for the audience, for the participants and for everyone involved. It also indicated a sense of connection and purpose, an environmental binding that crossed borders.

Each of these universities has had active environmental advocates and shared concerns about such issues as air pollution, pesticide contamination, and food and material waste. While climate change has not been as prominent, there have been indications that a small but determined core of climate youth activists have become visible in all three places.

At the same time, climate youth activism has taken hold globally in the past few years and has become a major backdrop at the various global climate gatherings, including the United Nations Climate Change Conference meetings in Madrid this year.

What the cross-border climate youth activism has yet to accomplish is more dramatic policy action and commitments from governments and institutions to reverse the trend toward a climate catastrophe. The climate youth activists, buttressed by scientific reports and studies, warn that such an imminent crisis is at hand.

Meanwhile, global greenhouse emissions increase each year. By championing global action, young activists are demonstrating that the climate crisis needs to be addressed not only locally and nationally, but globally across borders.

Right now, that's not happening. "Countries are exceedingly late for achieving pathways to close the emissions gap, with most measures so far having been incremental and gradual," says a 2019 UN "Emissions Gap" report. It argues that "deep transformations are now needed to peak global emissions immediately and commence the rapid decline toward net zero emissions by 2050". This would necessitate emission reductions by 50 percent every decade, a core target identified by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

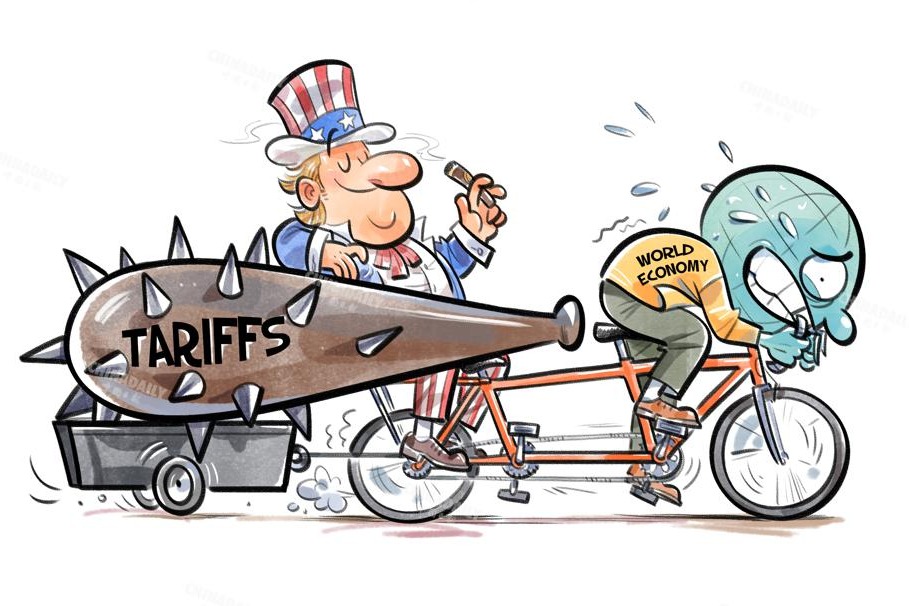

The actions of the United States and China are a case in point. The administration of US President Donald Trump has reversed modest climate policies undertaken by the previous administration. Trump himself has been a leading climate denier, even arguing at one point that climate change was a hoax perpetuated by China.

Climate-related policies and actions undertaken by the US state of California have helped, but have not been sufficient to reverse the nearly 3 percent rise in greenhouse gas emissions in the US in 2018. The 2019 emissions are on track to decrease in the US by about 1.7 percent, largely due to the collapse in coal-fired energy generation, but not enough to offset the 2018 increase and nowhere near the ability to reach a 50 percent reduction by 2030 and thereafter. To meet the IPCC goals requires far greater changes and a far deeper commitment to action in the years to come.

China has been able to slow the rapid increase in carbon emissions that took place during the 1990s. The country has established important climate-related policies and actions such as governmental support for renewables, a decline in the number of coal-fired plants, expansion of public modes of transportation, and a commitment to meet goals it established in the 2015 Paris agreement on climate change. Yet China's emissions will continue to increase through 2030.

Together, the US and China account for more than 40 percent of global emissions. If present trends continue, the two countries alone could create a worldwide temperature rise of 2 C or greater that could have catastrophic consequences.

What can happen to change that dynamic? For one, a shift away from the cold war environment between the US and China and toward a goal of cooperation and collaboration would be an important first step.

Growing public concern could be another factor. Such concern is lower in the US and China than in most other countries, though it is increasing, especially among young people.

In the US, 59 percent now see climate change as a major threat, up 19 points from 2013. And 71 percent of those ages 18 to 29 say climate change is a threat, compared with half of Americans 50 and older.

There are fewer studies about climate change awareness in China, though the most recent studies, including one published in China Quarterly in August, point to increased concerns, especially among young people.

The global climate youth movement has the potential to influence the course of events, both due to the growing number of participants and the recognition that climate impacts have a generational dimension. If policymakers would begin to listen to their young people, the ability to change course to avert a global crisis may still be realized.