Fearless about flying

By Mingmei Li | China Daily | Updated: 2024-12-23 07:16

Many Chinese Americans, born and raised in the US as citizens, chose to join the schools, pledging, as Ankeny writes, that dying for China would take precedence over any personal relationships that might develop.

"But I also think that Hazel considered herself mostly American. She was clearly Chinese American, but remember how young she was? She was a teenager, and she did all the things that American teenagers do. But after school, she went to Chinese school, and learned to speak Cantonese," Ankeny says, adding that she could feel Lee's attachment to her parents' country of origin.

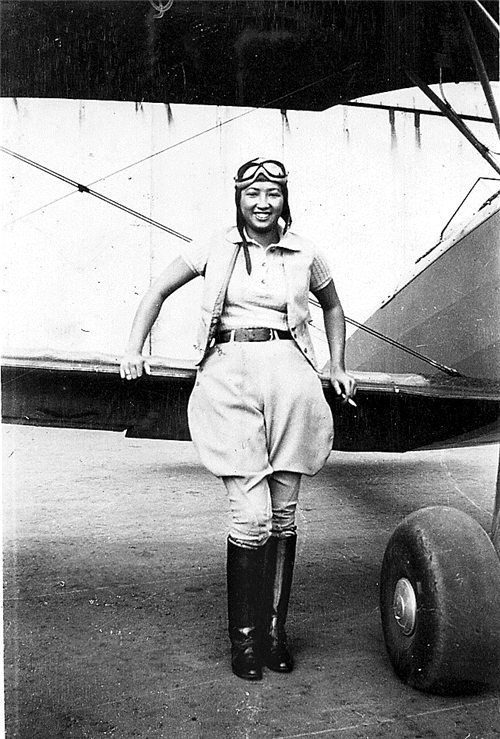

Chinese American pilots were rare, and female pilots were even rarer — but Lee was both.

"Hazel raised her hand to block the blinding glare. Her khaki coveralls — men's size 42, the only size available — enveloped her small frame. Even with the sleeves and pant legs rolled up and a belt cinched tight around her waist, the one-piece suit engulfed her … " Tate wrote in the prologue of the book, illustrating the issue female pilots faced with the lack of properly fitting gear.

Despite this, Lee earned herself a place as a pilot.

"The fifth floor of the H. Liebes& Co department store was not high enough for Hazel Lee, 20, and an elevator operator there, so she got up early each morning to learn to fly," says a clip in the archive of the Oregon Journal. At a time when elevator operator was one of the few jobs available to women, Lee's accomplishments were celebrated.

"She drank whiskey, she gambled, she smoked cigars, and yet people loved her. She loved dog fights. The adventure, the daring — that's what fed her soul," Ankeny says.

Lee wasn't the kind of girl who fit expectations; instead, she was entirely herself.

"She just stood her ground and asked questions like, 'Why can't I do this because I'm a woman? Why can't I do that because I'm Chinese American?'" Ankeny says.

Lee left for China with the rest of the team in October 1932, a year after Japanese forces invaded and occupied northeastern China. In addition to flying, she also wanted to visit her half-siblings, aunts, uncles and cousins who lived in her father's hometown of Taishan in Guangdong province.

However, as a woman, Lee was not permitted to fly in the Chinese Air Force. Instead, she was commissioned as an officer, and took on administrative roles, occasionally flying for commercial and private airlines.

In 1937, when Japanese forces began invading the rest of China, she was in Guangdong with friends and was forced to take shelter during bombing. She returned to the US to continue her journey as a pilot, while also working for the Chinese government as a wartime supplies buyer in New York.

When the US entered World War II following the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Lee joined the Women Airforce Service Pilots, a division of female pilots who flew noncombat missions. From February 1943, she was busy transporting military planes, undertaking ferrying and administrative flights, and pursuing her dreams.

Because they were classified as civilian noncombatants, even though they flew under military command, WASPs did not receive military benefits.

"She wanted to serve China, and then she wanted to serve with the United States military," Ankeny says. "She was showing us an example of how it doesn't matter what you look like, what you believe, where you come from. This is what's so great about this story — proving that you can be patriotic to more than one country. You don't have to pick."

Throughout her book, Ankeny mentions that Lee faced a significant degree of racism, and would likely have had a very different experience in China.

"You don't have to be Chinese American or any nationality or gender to know what it's like to be told you can't do something. It doesn't matter who you are. It doesn't matter — your color, your gender, your religion," says Ankeny. "She never let anybody say, you can't do that. And at that time in our country, that was even way braver than it is now.

"I was able to find few resources in China," Ankeny says, explaining that the war had interfered with record-keeping at the time. "But I hope I opened this up for Asian Americans. There's a lot more to research about Lee, and also about China."