|

|

Peter Hessler records his amazing experiences in fast-changing societies like China in his collection of essays Strange Stones: Dispatches from East and West. [Photo/Provided to China Daily] |

Storyteller Peter Hessler embraces humor to depict life in China. Writing in first-person narrative, Hessler's work now appears online and elsewhere in Chinese. Kelly Chung Dawson reports in New York.

On a visa run to Hong Kong in 1999, Peter Hessler made a stop in a tiny village with competing rat restaurants.

He was working as a freelance reporter at the time, and stories in the Chinese press about Luogang, in the southern province of Guangdong, had caught his eye.

At the Highest Ranking Wild Flavor Restaurant, a waitress casually asked Hessler a question he hadn't ever considered.

"Do you want a big rat or a small rat?"

At the next table, a little boy was contentedly chewing on a miniature drumstick. A small rat, then.

Later, the American e-mailed an account of his trip to a group of family and friends that included his former professor in narrative nonfiction, author John McPhee.

Only in the first person could Hessler do the story justice, the better to chronicle his experience of being wooed by rival rat eateries bent on conquering his foreign palate.

As he had discovered as a volunteer in the Peace Corps, humor wasn't just a coping mechanism in China, it was necessary for accurate depiction.

McPhee forwarded the e-mail to the editor of the New Yorker, David Remnick, who eventually hired Hessler as the magazine's China correspondent.

A version of that e-mail, now titled Wild Flavor, appears in a new collection of Hessler's essays. Fittingly, Strange Stones: Dispatches from East and West, is dedicated to McPhee.

"I take humor seriously," Hessler says. "We don't do this enough when we write about the developing world, and that gives people the impression that people in these places live dark, poor lives. There are funny things happening everywhere, and sometimes in the effort to be respectful writers can be condescending. We have to be able to laugh."

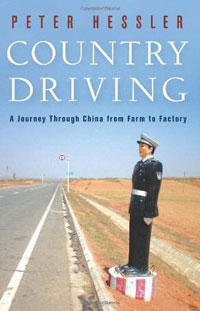

Hessler, who now lives in Egypt, is the author of three other books about China: River Town (2006), Oracle Bones (2007) and Country Driving (2011).

With Strange Stones, he expands his focus to Nepal, Japan and the US, in the hope of demonstrating that his interests don't begin and end in China.

In other essays he touches on life in Colorado, where he and his wife Leslie, also a writer, spent four years in between China and Egypt.

His position with the New Yorker affords Hessler the luxury of spending weeks and sometimes months on a story, he admits.

Unlike many journalists, tasked with breaking news and often at the mercy of translators and fixers when working abroad, Hessler put his fluency in Mandarin toward the slow cultivation of relationships with people in cities all over China during his tenure.

He had lived in a Beijing hutong (alleyway) apartment for more than four years before writing about the neighborhood's WC Julebu (WC Club), so named for its installation in a public restroom built in advance of the 2008 Olympics.

Hessler joined the club as a Young Pioneer, the highest rank eligible to him as a foreigner, he recalls dryly in the story Hutong Karma.

His experience of China was consistently shaped by the way people reacted to his ethnicity, he writes in the preface to Strange Stones.

As a result, first-person narrative seemed necessary in communicating an important part of the tale.

"Mostly though, I wanted to convey how things actually felt - the experience of living in a Beijing hutong, or driving on Chinese roads, or moving to a small town in rural Colorado," he writes.

"The joy of nonfiction is searching for balance between storytelling and reporting, finding a way to be both loquacious and observant."

Hessler, who grew up in Missouri with a father who loved to tell stories, observes that a major difference between Chinese and Americans relates to narrative.

In Colorado, new acquaintances were often prone to falling silent upon learning that he had spent over a decade in China. He found Americans to be much more comfortable talking about themselves.

In contrast, the less individualistic nature of Chinese culture often made his work in China more difficult. His Chinese subjects were surprised at his interest, and lacked the instinct for which details he might find interesting.

Chinese were more likely to be interested in his life in the US, a natural response to the opportunities that have become available to them over the last decades, he says.

"China is going through a period of intense curiosity, whereas since 9/11, the outside world has for many people in the US offered a threat," he says.

The occasional naivete of his Chinese subjects has made Hessler acutely conscious of trying not to exploit their life stories. He remains in touch with most of the people he has written about, some of whom have had complicated reactions to his essays.

The fact that his work now appears online and elsewhere in Chinese has also been a welcome development.

Although Hessler returned to Colorado after China in part to prove to himself he could still live in the US, he ultimately believes there is important work to be done overseas.

"In places like China and Egypt, they're still figuring out what direction they're moving in and who they are," he says.

"As a writer, it's an amazing opportunity to be able to spend real time with a society in the process of major change."

Hessler's works

records Peter Hessler's two years on the Yangtze River, in the remote town of Fuling. He was the first American to arrive in more than half a century. Teaching English at the local college, he wrote about the aspiring students as well as a radically different and developing society.

Oracle Bones

combs through his experiences in China from 1999 to 2002 with a handful of ordinary Chinese. The author follows their choices and changes in the quickly morphing society, intersecting his narration with maps and information about oracle-bone inscriptions or ancient Chinese writing.

Country Driving

is the final book in Hessler's China trilogy, where he looks at the country's farms and factories. He records how the country is building roads and factory towns, and investigates the status of migrant workers as well as concerns about urban development.