Days are numbered for ancient villages

By He Na and Sun Ruisheng in Shanxi province and Lin Jinghua in Beijing ( China Daily )

Updated: 2013-11-19

|

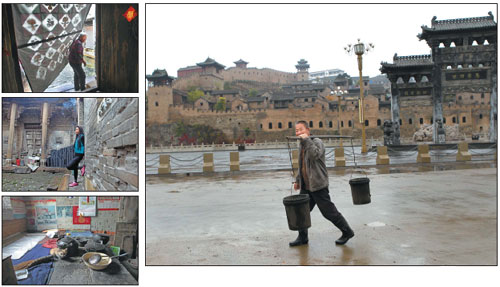

Above: Xiangyu village in Qinshui county, Shanxi province boasts fortress-like buildings from the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) Dynasties. Top left: Guo Xiaoju, 73, has been living in Lianghu village in Gaoping city, Shanxi province, since she was born. Middle: Lianghu resident Li Xinmei, 45, says she will move out of her old house if she can raise the money. Left: The interior of a typical house in Lianghu village. Photos by Zou Hong / China Daily |

A number of factors are to blame, report He Na and Sun Ruisheng in Shanxi province and Lin Jinghua in Beijing.

As part of humankind's historical heritage, traditional villages have high value in terms of research, architectural techniques and cultural continuity.

They can be seen as living fossils of China's agricultural and bureaucratic societies.

However, many traditional villages that were prosperous hundreds or even thousands of years ago are facing a crisis of decline, decay and even extinction.

In August, the ministries of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, Culture and Finance jointly launched a list of 915 traditional villages needing immediate help.

The list is an extension of one drawn up several years ago, but experts say the move is far from sufficient to save the villages and have called for more government help and practical protection measures.

Is it a case of survival or extinction?

China Daily reporters visited several experts, organizations and individuals providing financial support for the protection of traditional villages, plus residents, to seek their views on protection and the difficulties they face.

On a drizzling, windy November day the locals had all donned their winter clothing, but the doors of the houses in Lianghu village, 17 kilometers' east of Gaoping city in Shanxi province, were still open, covered only by thick cloth curtains that acted as windbreaks.

Lianghu is home to some 500 households and 1,542 villagers. The history of the former transport hub dates back to the Warring States Period (475-221 BC). Tian Fengji, a high official during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), built a castle-style house in the village, which also features a number of temples dedicated to different gods, including those who oversee safety, childbearing and study, which coexist peacefully. The village developed significantly during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) and reached its current size during the Ming Dynasty.

Seen from a distance, Lianghu's old courtyard-style houses, with the first floor for living and the second for food storage, appear well-preserved, but when you visit door to door, it's obvious that many of the gray brick walls are cracking and the dark brown wooden rails, roof and stairs are either split or partly rotten as a result of a lack of maintenance.

Walking along the narrow roads flanked by high walls, there is a distinct feeling of stepping back in time, but the sight of the new houses complete with pasted tiles on the external walls quickly brings you back to reality.

"If we had coal mines or another source of income, we wouldn't have so many dilapidated buildings here. With an increasing number of young people moving away, many abandoned buildings are in great danger of collapsing," said village Party chief Wang Yongshun, pointing at a pile of rubble and bricks. "That was once a well-built, beautifully decorated three-story house. Now all that's left is the gate. Whenever historical experts visit, they stare at the carved gateposts for a long time and murmur 'What a pity,'" he said.

Although it was noon, Zhang Jinquan's room was still a little dark. The 65-year-old sat against the wall and watched TV while his wife sliced vegetables for lunch in the dim light afforded by a carved window.

To keep warm, the couple lives and cooks in one room, but the line separating the cooking and sleeping areas is not very clear and things are scattered everywhere. Except for a few old newspapers on the wall, yellowed with age, the room has retained its original look from more than 400 years ago. Zhang's children have all married and moved away, but the elderly couple chose to stay in their home. "They thought the house was too poor and inconvenient. But for me it's better than anywhere else," said Zhang.

The couple owns a small field of 0.13 hectares, but the crops it yields doesn't even cover their medical bills, so Zhang often takes odd jobs at local businesses.

Mixed feelings

Bi Yueying, 73, lives alone, apart from her kitten. Her children tried to persuade her to move in with them, but Bi insisted on living on her own. "I don't feel lonely. All my memories are in this house," she said. "It's too noisy in the cities."

She lives in one small room, but always ensures that the bigger of her rooms, which contains two beds, is cleaned every day. "It's for my children," she said.

However, Bi's neighbor, Li Xinmei, 45, and her 20-year-old daughter would rather not live in their old house. "My daughter doesn't like the room at all and often complains that life here is too boring," said Li. "Of course I have feelings toward the house, but if we can earn enough money we will also move out."

Lianghu is symbolic of traditional Chinese villages, many of which are in a similar, or even more dilapidated, condition.

Statistics from the National Traditional Villages Conservation Commission show that around 900,000 traditional villages have disappeared during the past decade and the 12,000 villages that have applied for protection so far account for a mere 10 percent of the total number. Approximately 2.7 million traditional villages still remain in China, according to the Ministry of Civil Affairs.

Li Huadong, an associate professor at the School of Architecture and Urban Planning at Beijing University of Technology, is an advocate of protecting traditional villages. To his mind, their importance to the country is equivalent to that of oxygen, food and water to human beings.

"It's ironic that some villages survived thousand of years of war and disasters, but have disappeared in peacetime through demolition or people's short-term views," he said.

He explained that culture is the root of national power and the unbalanced economic and cultural developments will eventually lead to disaster. China's development must be based on history and traditional civilization and, as the fruit of ancestral wisdom, traditional villages are the root of Chinese culture, he said.

"Villages and cities are complementary. History tells us that the cities will die if the villages disappear," he added.

Lou Qingxi, director of the ancient architecture research center at Tsinghua University, often uses a metaphor for the protection of traditional villages during his classes, pointing out that it's frightening for a person to lose their memory, but that feeling is even worse for a village, a city or a country. China was established on an agrarian society and traditional villages are the country's living history.

"Why does the government expend so much energy on the Palace Museum? It's an architectural masterpiece, but more importantly, it witnessed, and is evidence of, China's politics, economy and culture through the course of history," he said.

"Traditional villages have the same function. They can help us understand history and learn the spirit and culture of our ancestors," Lou said.

Direct reminders of history

The protection of traditional villages doesn't only lie with the architecture, but also in unique elements that reflect the essence of Chinese culture, and in items rich in intangible cultural heritage such as festivals, clothing and tools, according to Lou.

He explained that China has more than 5,000 years of history, and documents only record some of that history. Compared with cities, a huge part of China's history happened in villages. Documents are indirect records, but traditional villages are direct reminders.

"Because of the limitations of transport and information in ancient times, China's rural culture and buildings have strong regional characters which can provide historical researchers with high-value evidence," he added.

A Yuan Dynasty stone tower is the landmark of Dazhou village in Gaoping city, Shanxi province. Historically, Dazhou was an important border town and most of the houses were built during the Ming Dynasty. Bluestone roads, high gray walls and black roofs are the main colors seen in the village.

The condition of most of the old houses, with their broken wooden thresholds, railings and beams, is not a cause for optimism. Some have collapsed, spilling piles of bricks across the grass.

"Our ancestors lived in the village for generations and our houses all look alike. Who could have known they would turn out to have a high value? If we had known earlier, more houses could have been saved," said Wei Guocheng, Party chief of the village.

"The county government hired some workers to repair the two temples in the village, but our houses were not included in the renovation plan," he said. "Repairs require traditional techniques and materials and the cost is too high for us. I hope the government or some wealthy benefactors will help us."

Cao Baoming, a member of National Traditional Villages Conservation Commission, said urbanization also poses a huge threat to traditional villages.

"Urbanization will be the theme of China's development for a long time. Sadly, some government officials misunderstood urbanization and thought the process involved demolishing old houses and building new ones. The central government should pay great attention to the issue and should instigate measures to stop urbanization bringing even more harm to high-value traditional villages as soon as possible," he said.

With an increasing number of young people moving away to work in cities, Cao said depopulation is another serious problem for traditional villages.

Xiangyu village in Qinshui town, Shanxi, once had around 1,000 residents but now only around 30 households exist, each with one, or at most two, occupants. The elderly residents have to walk a long way to buy vegetables and daily supplies.

"It's no joke that one traditional village disappears every month. I have been to a village in Jiangxi province where the population comprises just a few elderly people. The houses are locked, leaning over or collapsing. It's a village without smoke at cooking time," Cao said.

Xu Zhenjin, director of the Gaoping Housing and Construction Bureau, said, "China has a long history of farming, therefore we have a large number of traditional villages. It's unrealistic to use government funds to protect all of them and anyway protection requires the efforts of society as a whole. We plan to employ different methods, such as offering preferential policies, ceremonial positions or naming rights to encourage more social organizations to become involved."

Li Huadong echoed Xu's opinion and said the only solution is for villages to attract more funds from social organizations.

"However, the current land policies in rural areas don't allow villagers to transfer ownership, which has become a big obstacle stopping traditional villages from entering the property market and has also dampened many people's enthusiasm to explore tourism opportunities or protection," he added.

For Lou, protecting a traditional village is a more difficult task than protecting the Forbidden City.

"The Forbidden City has lost its original function as a government center, therefore its protection is only focused on architectural maintenance and fire prevention. But people still live in the traditional villages and we need better planning and more help," he said.

Contact the writers at hena@chinadaily.com.cn and linjinghua@chinadaily.com.cn