What does end of QE mean for EMs?

By Neil Shearing (China Daily) Updated: 2014-11-03 07:39

Most of the emerging world should take the end of the US Federal Reserve's third phase of quantitative easing in its stride. The link between QE and capital flows to emerging markets has often been exaggerated. And while some emerging markets look vulnerable as rates in the United States move up, it's far more likely that growth in the major EMs will be held back by homegrown problems than by the actions of the Fed.

The Fed confirmed the end of its asset purchases under QE3 on Oct 30. Anticipation that it would start to scale back purchases proved the trigger for last year's "taper tantrum" in which markets across the emerging world fell sharply. Looking ahead, the majority view appears to be that the end of policy stimulus in the US will pose a stiff headwind for EM growth in the coming years.

We at (Capital Economics) would be wary of dismissing the potential fallout from the end of QE and the eventual tightening of US policy altogether. But the worst fears that it could trigger a spate of crises across the emerging world are overdone. Our Global Markets service is the place to look for detailed analysis of what impact QE has had on EM financial markets, but the short point is that it does not seem to have been a major support for equities.

Accordingly, there is no compelling reason to expect EM equities after QE ends. In terms of the macro fallout, there are two channels through which QE might have had an impact on EMs. The first is by providing much-needed support to the US economy, although with the recovery now on a firmer footing this has become less important. The second is by boosting capital flows to EMs.

The evidence here is mixed. It does seem that inflows to EMs picked up in all three phases of QE. Even so, we would be careful about overplaying the extent to which this has been an important driver of capital flows to the emerging world. For a start, inflows continued to rise after the end of QE1 and before the start of QE2. What's more, despite three rounds of QE, inflows remain well below their pre-crisis peak. In other words, the scale of inflows to EMs is determined by more than monetary policy - unconventional or otherwise - in the US.

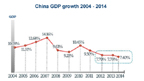

Given this, it would be wrong to draw a mechanical link between QE and the economic performance of EMs. Indeed, EM growth slowed during the second phase of Fed QE and has remained extremely weak throughout QE3.

In practice, it's impossible to construct a one-size-fits-all view of what the end of QE means for EMs. QE, along with super-loose policy in the US more generally, has enabled some EMs to borrow cheaply to finance consumption binges and sustain large current account deficits. This will become more difficult as US rates start to move up. Countries with large external borrowing requirements, including Turkey, Indonesia and South Africa, are likely to come under pressure.

But we suspect the bigger theme in EMs in the coming years will be continued weakness in the BRICS member states. These countries are by far the largest emerging economies and they are all struggling for domestic reasons. And reviving growth in BRICS will depend on the actions of local policymakers - not those in the US.

The author is chief emerging markets economist at Capital Economics.