Rapid rise thanks to balanced structure

By Fang Ning (China Daily) Updated: 2014-12-16 08:49Economic freedom and political centralization have enabled China to weather the storms it has encountered over the past 30-plus years

The mere mention of China can arouse controversy. Many comments have been made about its rapid economic and social transformation over the past three and half decades.

But for Fang Ning, a political scientist with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the Chinese experience is the balanced structure of "economic freedom plus political centralization".

The structure has got "increasingly clear" since Xi Jinping became leader of the nation in late 2012, said Fang, director of the institute of political science at the academy, in his interview with China Daily.

Some people interpret China as autocracy or high-handed State capitalism. But Fang said those terms, along with the selective descriptions attached to them, are "inaccurate", and do not summarize the Chinese experience as neatly as they might appear to.

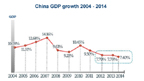

They can't explain the country's success in having managed to avoid some major stumbling blocks, the most recent being the 2008 world financial crisis and the following changes in the global trade system.

China's success "lies in its economic freedom as much as in its strong central government," but that is not a Chinese invention.

"In fact," Fang argued, "few, if not none, of the developed countries today show a different historical experience (from China's) in having economic freedom plus political centralization or re-centralization when they entered modernity. Democracy didn't evolve from the outset."

The same is true of the relatively more successful cases among developing countries, such as Singapore and South Korea, he said.

"Economic freedom combined with political centralization is most suitable to the country's realities," Fang said when he spoke about China's present stage of transformation. "And we say this precisely because we have taken note of the democratization process in the West."

Fang said premature political democratization has often resulted in chaos. "Democracy is a good thing, admittedly. But it can't be the only value to strive for. It can neither be unconditional nor absolute. Because no one can say it's a case of the more the better, and that you can have it in infinite ways. Nor can it be something that trumps other values."

At an early stage of a society's modernization, some forms of democracy, such as general elections, inevitably result in prolonged political instability and even upheaval, due to the widening and increasingly intense division in the interests of different sectors and groups, as seen in Europe in the 19th century, and in some of the post-revolutionary societies in today's world, Fang noted.