Rise and fall of Japan as a leader in science research

By Cai Hong (China Daily) Updated: 2015-10-26 07:42

|

|

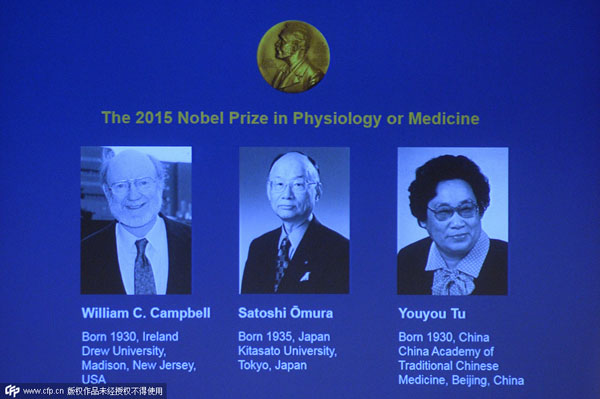

William Campbell, Satoshi Omura and Tu Youyou jointly won the 2015 Nobel Prize for medicine for their work against parasitic diseases. [Photo/CFP] |

The Nobel Prize in medicine or physiology that Chinese scientist Tu Youyou won early this month made her compatriots jump for joy, and she deserves high praise for the honor.

Along with Irish-born William Campbell and Satoshi Omura of Japan, the Chinese scientist was awarded the prestigious prize for discovering drugs against malaria and other parasitic diseases that help hundreds of millions of people every year.

The award of a Nobel Prize is an honor to the individual laureate, but also to the institution and country concerned.

Japan is third in the global league table of 21st century Nobel Prize winning nations in science, according to the magazine Times Higher Education, with the United States way out ahead in the first place.

The table, which includes 146 laureates since 2000, ranks countries according to the nationalities at birth of Nobel Prize winners in the fields of economics, medicine, physics and chemistry.

Takaaki Kajita of the University of Tokyo won the Nobel Prize in Physics this year, the seventh year in which the Nobel Prize in Physics had been awarded to at least one Japanese recipient.

In 2001, the Japanese government set a goal of garnering some 30 Nobel Prizes in 50 years. Half of that target has been reached in 15 years.

Japanese scientists' extraordinary persistence and academic strength are acclaimed worldwide. But even while giving their laureates a pat on the back, some in Japan are predicting the prospects for more awards are not very promising. Kyodo News worries about the Japanese government's shrinking funding for national higher learning institutions and a shortage of new blood flowing into research institutes.

The Sankei Shimbun says the prizes Japan wins today do not necessarily indicate its academic strength, as the recipients usually did their prizewinning work 10 to 50 years ago. The Mainichi Shimbun criticizes the merit-based pay system that is becoming prevalent in the country's research and development. As a result, it is increasingly difficult for Japan's researchers to conduct time-consuming and creative research.

Japan's experts warn that in physics, chemistry, biology, material science and space science, the number of research papers from Japan and citations for them started dropping sharply in the mid-2000s, compared with those from the United States, China, the United Kingdom, Germany, France and the Republic of Korea.

They highlight Japan's fall and China's rise as a research superpower based on the Thomson Reuters' InCites database. Japan produced 12,534 papers among the world's total of 121,739 papers in 1982, ranking second after the United States in the number of research papers in the five science fields.

Back then, China produced only 629 papers. In 2011, things changed. Japan's standing had slipped to fourth, accounting for 31,487 of the world's 392,074 papers. While China leapfrogged many nations to claim second place, with 76,664 papers.

All these factors make some people in Japan fear no more Nobel Prizes will be coming to their scientists over the next 10 or 20 years. They claim that their country's prize spurt suggests the danger of judging too soon which nations are doing the most significant basic research.

China, meanwhile, has declared the creation of world-class universities as national policy objectives. It has the educational and intellectual potential and political will to achieve this. Winning Nobel prizes would be the crowning successes of these longer term policies. To know for certain the innovation leaders of today, we might have to watch for the Nobel winners through 2060.

The author is China Daily's Tokyo bureau chief.

caihong@chinadaily.com.cn

I’ve lived in China for quite a considerable time including my graduate school years, travelled and worked in a few cities and still choose my destination taking into consideration the density of smog or PM2.5 particulate matter in the region.