This is the 13th year Dong Shuzhen has left Beijing on an eight-month trip to help blind people in remote areas see again.

Dong is in charge of a set of four four-carriage eye hospital trains, supported by an NGO called Chinese Foundation for Lifeline Express, which was founded in 1997 in Hong Kong. At the time, it received enough funding from citizens and local government to buy a single train.

Shortly after it was set up, the NGO was passed to the mainland as a present to mark the return of Hong Kong. A local branch was later established in 2002, called the Beijing Foundation for Lifeline Express.

Another three trains were bought from money donated by companies including Sinopec and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China.

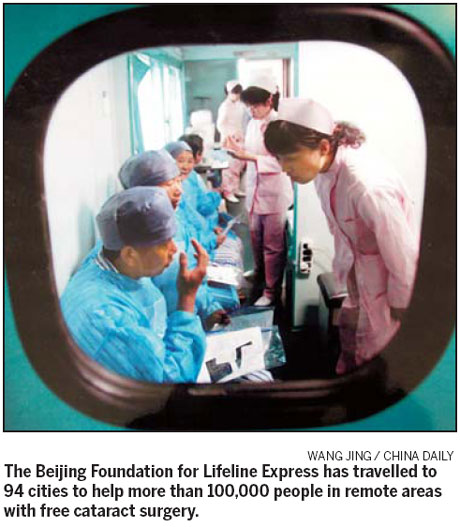

The trains have now traveled to 94 cities, and have provided free cataract surgery to more than 100,000 people in remote areas of China.

Each train comprises a surgery room, two bathrooms and a resting carriage for 40 patients.

Between five and 10 experienced doctors from top eye hospitals handle the workload. On the side of each carriage is painted a rainbow.

The year's journey began on March 22 when the first train left from Beijing East Railway Station to Mianzhu, Sichuan province. By the end of March the other three trains left for 11 remote areas in seven provinces.

The trains return to Beijing in November and remain until March while the winter passes. This means workers like Dong only have four months to be with their family members.

"But I love the job. I love bringing light to patients. Perhaps I can't help the whole nation, but I can at least bring hope and love to remote areas," she said.

Doctors and nurses stay on the train for months at a go. With only a toilet-sized room to sleep in, the only regular habit on offer is taking a bath.

"They are necessary because we need to prevent against contamination in surgery," said Wang Zheng, director of the ophthalmic department of Beijing Hospital, who joined the group in early 2005.

At that time, Wang left her four-month-old daughter in Beijing to help patients in Gansu and Guizhou provinces.

"When I came back half a year later, my daughter couldn't recognize me and kept crying," she said.

This time around, she joined the project to Luoyang, Henan province, on March 27, leaving her daughter at home again.

"I was green five years ago, but this time, I'm going to give guidance to three new doctors," she said.

Wang told METRO many patients in remote areas have never bathed before.

"We were bitten by fleas and other bugs. Some doctors couldn't sleep at night," she said.

"But it is a meaningful job. Without our work, some patients would never see this colorful world."

Due to the time limitation of each medical checkup, each patient can only receive free cataract surgery on one eye. This means some patients have to wait years to get full vision.

Dong said that people living in urban areas always use social connections to try to get surgery done on both eyes. She was surprised by the attitude of patients in Tibet.

"They refused to do surgery on both eyes, even if we gave them the chance. They believe God has given them a basic chance to see, but they shouldn't be too greedy," she said.

"They taught me to be a simple and contented woman, to appreciate the kindness of humanity."

Over the past year, the Chinese Foundation for Lifeline Express has also built two permanent cataract medical centers in Sichuan and Guangdong provinces - training hospitals in which doctors get three months practical experience - offering long-term medical assistance to low-income patients.

Liu Menglin, press official with the foundation, said nine more centers in the provinces of Henan, Jilin and Qinghai, as well as in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, would be built by the end of the year.

Medical apparatus worth more than 7 million yuan would be available at the centers.

In addition to the medical staff, volunteers are also getting involved in the program.

"I joined in 2008 after being introduced by a friend. I try to raise public awareness through my photography," said Huang Jianjun.

He said he took his 13-year-old son to travel on the train to several poor areas in China.

"What we did was only a small step, but if it helps a patient to see again, it was worth it," he said.