|

Gu Qi and his girlfriend Mo Bai relax in their home, which also serves as a furniture showroom. [Photo/China Daily] |

|

The living room has a long chest of drawers and a classically-styled wooden chair. |

|

A small cupboard and a simple chair, designed by Gu. [Photo/China Daily] |

Stepping into Gu Qi's home is like entering a home furnishings catalogue. The impression is completely realistic, since interior designer Gu actually lives in a showroom - a flat full of his own designs and also the place where he creates his works.

The 110-square-meter home, which has a modern Chinese design to it, has no signature objects on display - a feature many other young designers are using to declare their cultural identity, such as complex ornamental engravings and antique vases.

Instead, visitors will experience an atmosphere of quietness, elegance and perhaps even a little Zen.

On show are unpretentious wooden tables and chairs, bearing clean shapes and smooth lines that suggest strength in simplicity.

The house employs light colors only, such as white, beige and azure, communicating a peaceful mood.

Chinese ink paintings, created by Gu's girlfriend Mo Bai - a graduate of the China Academy of Art and currently a book cover designer - hang in all the right spots.

There are also some old-fashioned details, such as cream-colored flax curtains and porcelain utensils, which contribute to the sense of Zen.

Fan Ji, the brand name Gu has registered for his designs, is straight to the point.

Fan means "peace", and together with Ji - an ancient Chinese word for "furniture" - the two-character term speaks for Gu's belief that simple furniture can blend easily into everyday existence.

It goes deeper though, as an indication of Gu's personal struggle with a paradoxical trend that young Chinese designers are returning to a tradition and cultural identification.

On one hand, Gu said he is pleased to see how Chinese culture is now of utter importance to local artists. However, he's upset that too many young designers achieve this by pasting cultural symbols onto designs that are based on a Western nucleus.

In one of Gu's favorite photos, taken by the end of the 19th century, some Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) people sit on chairs designed by renowned European artist Michael Thonet.

"The scene doesn't look abrupt at all," Gu said.

He said at that time, though China was economically inferior, its acceptation of Western culture was based on a firm insistence of its own traditions. Gu believes the balance might be lost with some new designers, but his own interpretation is steadfast.

"Chinese furniture takes on a different function, of how to coincide with its surroundings," he said.

Easily the best way for products to look natural, in Gu's eyes, is for them to be made of natural materials such as wood, without the addition or even a need for padding. This is a traditional standard.

"All (my materials) are imported," he said. "The wood I use includes American Manchurian Ash, American Walnut and Myanmar Teak."

"These countries have steady drying technologies that often ensure good quality."

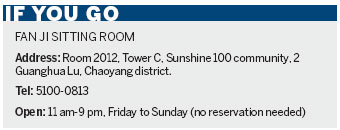

Gu's home, filled with his own particular understanding of Chinese culture, is open to visitors on weekends for free. He said there is a growing supply of interested customers.

Living in an flat comprised of his own designs, Gu said visitors can order a replica of any piece and have it delivered within 30 days.

"I (used to) follow customer suggestions when designing homes for them, but in this new business, customers come to follow me," he said. "Of course, they can still require some changes."

As his first group of customers eagerly wait for the delivery of their goods on Dec 20, Gu continues to tap into a growing trend of design-conscious individuals through his personal blog and a page on douban.com, a gathering place of young hipsters.

"I am happy to see that the country's youth are returning to the pure nature of an excessively interpreted culture."