With the country's dramatic economic growth and rising living standards more people in the south of China are demanding central heating to keep them snug in winter.

China, based on historic experience, is geographically divided into North China and South China along the Qinling Mountain Range and the Huaihe River. Winter in the north is much colder and lasts much longer than in the south, and a public heating supply system was established as a necessity in North China, while people in the south still have to find their own means to stay warm. Such an arrangement was a compromise due to China's economic strength in the 1950s when the heating system was introduced in the north.

|

|

At that time South China enjoyed shorter winters based on the criteria that it had less than 90 days in one year when the temperature dropped below 5 C. A determining factor when the Qinling-Huaihe North/South division was drawn up. However, climate change means the winters have been getting colder in South China, and many cities in the south of the country now meet this criteria. This fact has prompted calls for a public heating system in the south.

However, Jiang Yi, a professor at the School of Architecture, Tsinghua University, says there are a number of reasons why introducing a public heating system in South China isn't practical.

A large amount of heat loss has long been an intractable issue for the heating system in North China. According to Jiang, about 15 to 30 percent of heat is lost along the huge supply network or due to the unnecessarily high heat supplied in some places.

Jiang says there are a number of factors that would exacerbate the heat loss if a similar heating system was introduced in the south.

The walls of the buildings in South China are thinner than those in the North and therefore heat loss is faster. One of the few ways to combat this is painting a thermal insulation coating on the buildings, which would be costly.

Also people living in the southern areas are used to having their windows open more than people in the north and this would result in a considerable amount of heat being lost.

In addition, the winters are shorter in the south, so a public heating system would only be operational for one to two months. It would be unfeasible to spend huge amounts of money necessary to build, run and maintain such a system just for two months a year, Jiang says.

In North China, people pay about 2,000 to 3,000 yuan (($322-478) for central heating in a winter, while it costs people in the south about 600 yuan to 1,000 yuan to get warm in winter using air conditioners, electric radiators or heaters. Would people be willing to pay higher price for government-supplied heating?

However, what really vetoes any possibility of public heating for South China, Jiang says, is the impracticality of laying a pipe network in today's cities. The disruption it would cause in Shanghai, for example, is just unimaginable.

Reform has been brewing in the past decade to change the charge for heating in the north from heated area to the amount of heating supplied. This would raise the price and most people have opposed the idea.

However, the reform is going to be launched sooner or later, and on this point, extending central heating to South China would be at odds with the country's energy conservation policy, Jiang says.

Jiang suggests the government input more effort and funds in the south into insulation for buildings rather than splurging on a public heating supply system.

Sooner or later, reform of the public heating service in the north will be implemented to charge based on market pricing. This will ease the government's economic burden, increase heating-supply enterprises' profits, allowing them to adopt equipment with higher energy efficiency, while raising residents' awareness of the need to save energy.

The author is a journalist with China Daily

hebolin@chinadaily.com.cn

'Cat model' to dazzle Shanghai auto show 2013

'Cat model' to dazzle Shanghai auto show 2013

Models at Tokyo modified car show

Models at Tokyo modified car show

Shanghai Fashion Week focuses on domestic brands

Shanghai Fashion Week focuses on domestic brands

Angel-dress models at Shandong auto show

Angel-dress models at Shandong auto show

Safe and Sound

Safe and Sound

Theater firms scramble for managers

Theater firms scramble for managers

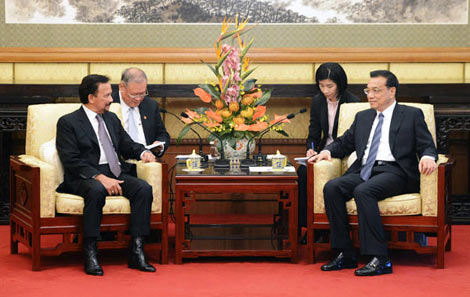

Premier pledges closer ties with Brunei

Premier pledges closer ties with Brunei

Volkswagen's all-new GTI at New York auto show

Volkswagen's all-new GTI at New York auto show