How can US go on leading the world?

By Andrew Sheng (China Daily) Updated: 2014-08-26 06:54Eighteenth-century German military strategist Carl von Clausewitz defined war as the continuation of politics by different means, and, like ancient Chinese strategist Sun Tzu, believed that securing peace meant preparing for violent conflict. As the world becomes increasingly tumultuous - apparent in the revival of the military struggle in Ukraine, continued chaos in the Middle East and rising tensions in East Asia - such thinking could not be more relevant.

Wars are traditionally fought over territory. But the definition of territory has evolved to incorporate five domains: land, air, sea, space and, most recently, cyberspace. These dimensions of "class war" define the threats facing the world today. The specific triggers, objectives and battle lines of such conflicts are likely to be determined, to varying degrees, by five factors: creed, clan, culture, climate and currency. Indeed, these factors are already fueling conflicts around the world.

Religion, or creed, is among history's most common motives for war, and the 21st century is no exception. Consider the proliferation of jihadist groups, such as the Islamic State, which continues to seize territory in Iraq and Syria, and Boko Haram, which has been engaged in a brutal campaign of abductions, bombings and murder in Nigeria. There have also been violent clashes between Buddhists and Muslims in Myanmar and southern Thailand, and between Islamists and Catholics in the Philippines.

The second factor - clan - is manifested in rising ethnic tensions in Europe, Turkey, India and elsewhere, driven by forces like migration and competition for jobs. In Africa, artificial borders that were drawn by colonial powers are becoming untenable, as different ethnic groups attempt to carve out their own territorial spaces. And the conflict in Ukraine mobilizes the long-simmering frustration felt by ethnic Russians who were left behind when the Soviet Union collapsed.

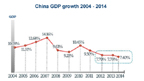

The third potential source of conflict consists in the fundamental cultural differences created by societies' unique histories and institutional arrangements. Despite accounting for only one-eighth of the world's population, the United States and Europe have long enjoyed economic dominance - accounting for half of global GDP - and disproportionate international influence. But the rising new economic powerhouses will increasingly challenge the West, and not just for market share and resources; they will seek to infuse the global order with their own cultural understandings and frames of reference.

Of course, competition for resources will also be important, especially as the consequences of the fourth factor - climate change - manifest themselves. Many countries and regions are already under severe water stress, which will only intensify as climate change causes natural disasters and extreme weather events like droughts to become increasingly common. Likewise, as forests and marine resources are depleted, competition for food could generate conflict.

This kind of conflict directly contradicts the promise of globalization - namely, that access to foreign food and energy would enable countries to concentrate on their comparative advantages. If emerging conflicts and competitive pressures lead to, say, economic sanctions or the obstruction of key trade routes, the resulting balkanization of global trade would diminish globalization's benefits substantially.